How Certain is Certain? When Scientific Data is Significant

When does new data disprove an established scientific theory? When can unexpected results be written off as coincidence or as inaccuracies in the measurements? How much evidence do you need to have in support of a new theory before accepting it as truth?

These are extremely important questions for scientists of all disciplines. Drawing the correct conclusions from data can be one of the most difficult parts of science.

An Analogy

Imagine that your friend gives you a bag of marbles, and tells you that the bag contains 1999 red marbles and only one blue marble. If you put your hand into the bag and pull out a blue marble, you might be suspicious that your friend lied to you about the contents of the bag.

You are suspicious because you know that the probability of you pulling out a blue marble, assuming that what your friend told you is true, is only 0.5%.

However, imagine that a whole room full of people have been given bags and told that each bag contains 1999 red marbles and 1 blue marble. You would probably be less surprised to see someone pull out a blue marble, even though the probability of any one person doing so is still only 0.5%. The probability of anyone in the room getting a blue marble is 0.5% multiplied by the number of people in the room.

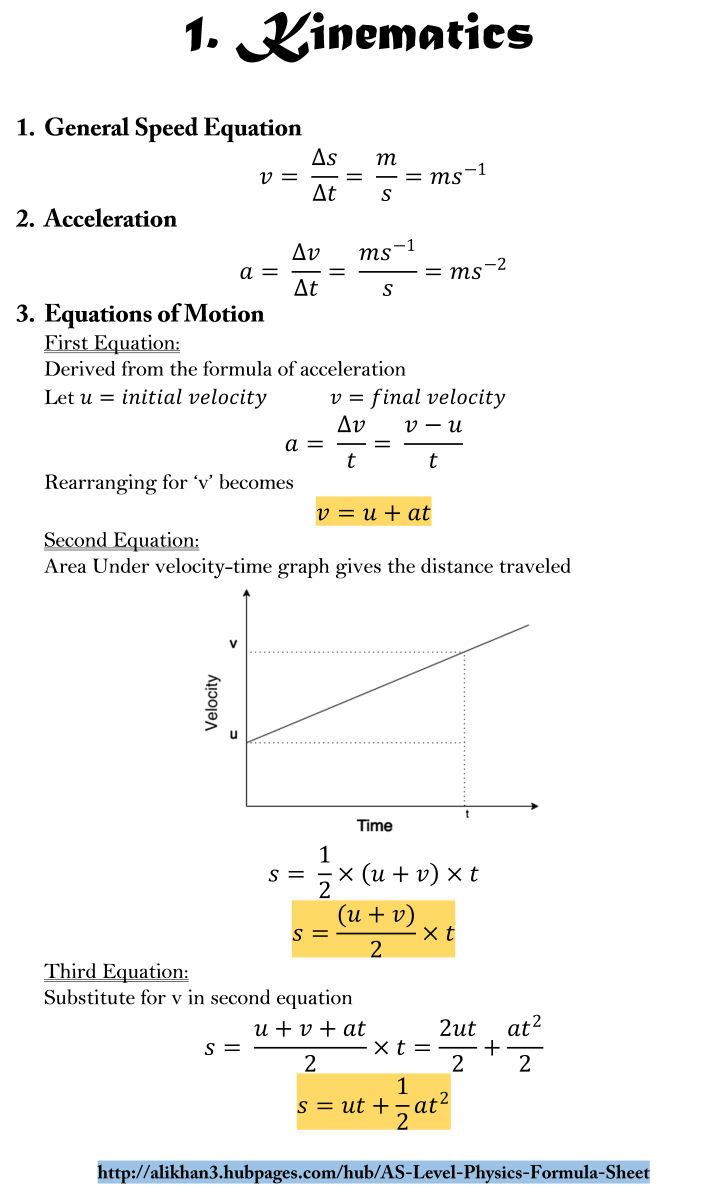

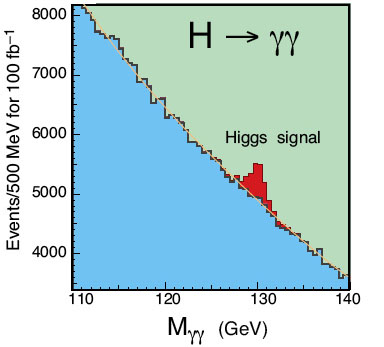

The peak in the LHC data has only a 0.5% probability of occurring by chance at the particular energy that it occurred. However, the total probability of a random peak occurring anywhere in the range of energies tested is much higher (about 8%).

The way to become more certain is to repeat the experiment. In the case of the marbles, you may want to make the person who drew out the blue marble put it back into the bag, shake up the bag, and draw out another marble. If the bag really does contain 1999 red marbles and only 1 blue one, it is unlikely that he will get blue again. If he keeps getting blue marbles, it is time to conclude that you have been lied to about the contents of the bag!

Similarly, researchers at the LHC need to keep collecting data to see whether they see further peaks occurring at the same energy. If they do, this will be strong evidence for the Higgs, because the probability of the same coincidence happening over and over again is very low.

As an example, there have recently been reports of data from the Large Hadron Collider that could be interpreted as evidence for the Higgs Boson - please also see:

Researchers working on the ATLAS experiment at the LHC have quoted the significance level of their results as 2.8 sigma – this means that there is a 0.5% probability that the result is due to random statistical fluctuation rather than the presence of the Higgs Boson.

The convention in particle physics is to discard an old theory and accept a new one only if the significance of an experimental result is 5 sigma – i.e. if the old theory predicts that the observed result will occur 0.00003% of the time. On this basis, the theory of “no Higgs” is a long way from being discarded.

Why so stringent? After all, when an experiment gives a result that the "no Higgs" assumption says should only occur 0.5% of the time, it becomes sensible to ask whether it would be better to accept the assumption that there is a Higgs.

However, there is another effect at work. The researchers can't see the Higgs directly, so they look for pairs of particles that could have been produced by a Higgs boson decaying. The energy of the pair of particles will be equal to the mass of the Higgs, according to Einstein's E=mc2 relation.

Because the physicists don't know what the mass of the Higgs is, they search for pairs of particles with energies in a wide range. If they find more pairs than expected with a particular energy, and work out that the chance of that excess occurring by chance is only 0.5%, they might conclude that the excess have been produced by a Higgs boson.

However, researchers have to be careful when drawing this conclusion. They also need to take into account all of the energies for which they didn't see an excess of particles.

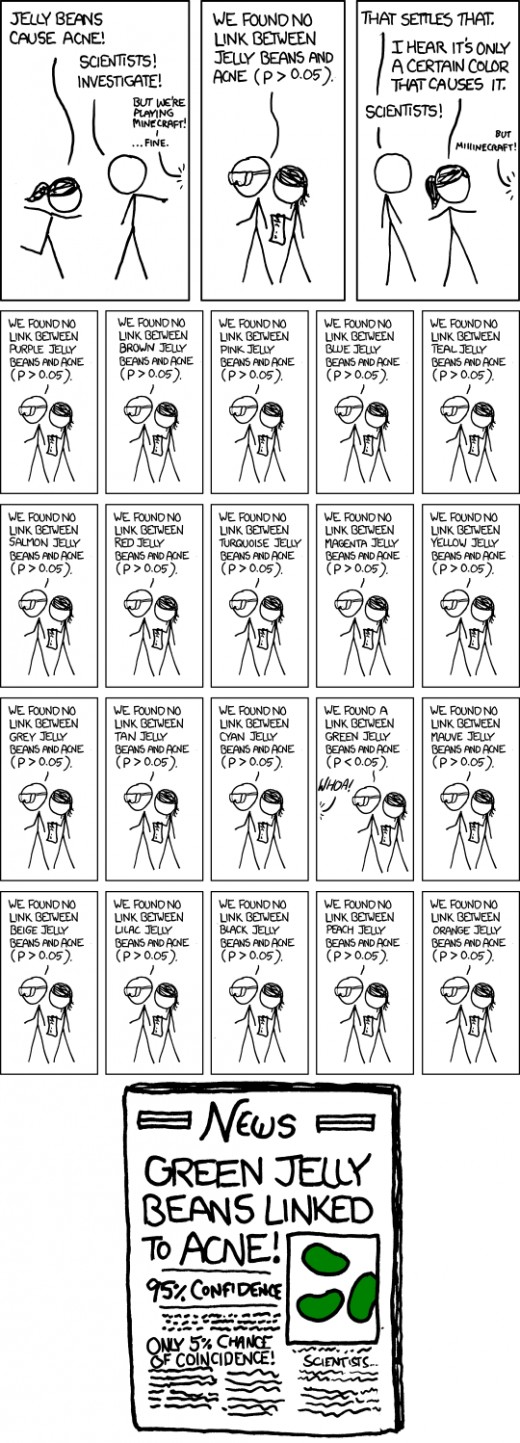

To see why, read the analogy in the box to the right, and enjoy this comic from xkcd:

What the comic is saying is that the correlation (between green jelly beans and acne) has only a 5% chance of being a coincidence, but because 20 experiments looked for these type of correlations, it's hardly surprising that one such coincidence popped up. In fact, one 5-per-cent-chance-of-coincidence correlation per 20 experiments is exactly what you would expect to see if there were no connection between jelly beans and acne whatsoever. (The comic also implies that the media don't always have the best understanding of this effect!)

The Higgs theory doesn't predict exactly what mass the Higgs Boson should have. So researchers have been searching for it at a range of masses. If you search for the Higgs at 120 GeV, 125 GeV, 130 GeV, etc, this is a bit like testing all the different colors of jelly beans. The peak in the data from the ATLAS experiment has only a 0.5% probability of randomly occurring at the particular energy that it occurred. However, the total probability of a random peak occurring anywhere in the range of energies tested is much higher. This is known as the "look elsewhere" effect.

Taking the look elsewhere effect into account, the chance of the ATLAS result occurring due to random statistical fluctuation is about 8%.

The thing that makes the result more likely to be significant, rather than something that can be explained away by statistics, is that there are two experiments at the LHC - ATLAS and CMS - that are reporting evidence for the Higgs in the same mass range, although the CMS evidence is not as strong. When several different experiments report the same result, we can be much more certain of its significance, because it is unlikely that the same coincidence will occur in all the experiments. Although it is possible that a systematic error (such as an error in the way the data is analysed) caused both ATLAS and CMS to report a false Higgs signal.

If more glimpses of the Higgs Boson come to light, they will eventually add up to conclusive evidence of its existence. At the moment, it's still too early to tell.

*source: conference proceedings, as reported at profmattstrassler.com/2011/07/22/atlas-and-cms-summarize-their-higgs-searches/